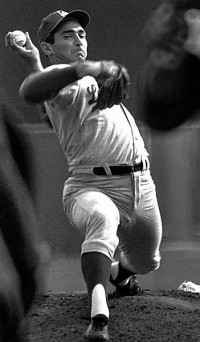

Koufax, bringing the four-seamer. God save the guy at the plate.

Author’s note: In honor of Koufax Day (anniversary of the day he skipped a World Series start b/c it was Yom Kippur), I repost this piece that originally ran in the old Neuron Culture May 2009. See also my follow-up on Koufax as god, with Most Incredible Pitcher Stats Ever and a vid of Sandy bringing it. Meantime:

I always look forward to the Illusion of the Year contest, but this year brings a special treat: a new explanation of how the curveball baffles batters.

Just a few days ago, during BP, my friend Bill Perreault threw me one of those really nasty curves of his, and though I read it about halfway in, I was still ahead — and still unprepared for the sudden slanting dive it made at that last crucial moment. The good curves do that: Even when you have that millisecond of curveball detection beforehand, they still seem to take a bend sharply and suddenly late in their path, as if some invisible hand gave them an extra tap.

This wonderful “illusion” — really an explanation via an illusion put together by Arthur Shapiro, Zhong-Lin Lu, Emily Knight, and Robert Ennis — explains how that happens. The curveball kills you two ways: through actual movement and an extra perceived movement that further complicates the task of getting that tiny strip of sweet spot onto the ball. (The sweet spot on a bat is about a half-inch tall and maybe 6 inches long. You have to get that small strip, which is over 2 feet away from your accelerating hands, onto the ball …. at just the right moment, and with the bat accelerating, or you’re probably out.)

I can’t paste the illusion in here, but suffice to say that certain visual dynamics — a difference between the neural dynamics of central vision and peripheral vision — cause you to see a baseball that is rotating horizontally but falling vertically appear to fall vertically if you’re looking straight at it — but moving slantwise sideways if it’s in your peripheral vision. Batters can’t completely keep up with a thrown pitch as it approaches them and it effectively accelerates its path across their field of vision (from coming at them to moving past them). So at the crucial moment — the last part of the ball’s path — you are essentially trying to track this baseball, which is usually in flight for a half-second or less, with your peripheral vision. It is in this fraction of a second — in which the ball would be hardest to track anyway — that the curveball actually moves the most — and in which its real downward and sideways motion is suddenly exaggerated as it moves into your peripheral vision (cuz your eyes can’t quite keep up).

That’s why Bill’s curveball was so untouchable. And that’s why the unexpected curveball, which arrives later than you expect, sharpens its effect all the more and seems to just jump downward.

All of which reminds me of a great story Jane Leavy told in her splendid biography of Sandy Koufax. World Series in either 61 or 62, Koufax is facing the terrifying Mickey Mantle. Book on Mantle is never, ever throw him the curve, for even though you may fool him badly, he’s so strong that he can still crush the ball even if his body is fooled but his hands are still not committed. So just don’t throw it to him. Koufax faces Mantle three times and throws all fastballs. (The best fastballs ever known.) Third time up, crucial situation, he gets two strikes on Mantle — and then shakes off the fastball sign, twice. Catcher catches on, puts down two fingers to call for the curve — which was a horrid thing, a nose-to-toes diver that just killed batters, best curve in the game … but still, he’d been told NOT to throw this thing to Mantle. But he does. Ball comes in eye-high, then dives, crosses the plate at Mantle’s knees. Mantle flinched a bit but never moved. Called strike three. He stands there an extra second, then says to the catcher, “How the fuck is anybody supposed to hit that shit?” and walks back to the dugout.

Oh Sandy.

See also my follow-up on Koufax as god, with Most Incredible Pitcher Stats Ever